D Home Publikationen G lastöpferei Techniken Kameoglas Diatretglas H edwigsbecher Craqueléglas Werdegang D

E EnglishHome Publications GlassPottery Techniques CameoGlass CageCups HedwigBeakers Craquele Vita E

Rosemarie Lierke

Antike Glastechnologie / Ancient Glass Technology

Cameo glass

The visible manufacturing traces and their explanation

Text I. Cameo glass - more evidence of molding (with a supplement)

Text II. How about an earlier date for some cameo glasses?

Publications on ancient cameo glass by Lierke and others: L1996a (first description of hot forming); L1997b (short article in Annals AIHV); 2 papers on “Recent Investigations of Early Roman Cameo Glass” in Glastechnische Berichte: I. Lierke/Lindig 1997 (manufacture, first investigation of the internal scratches); II. Mommsen et al (X-ray fluorescence analyses;Glastech. Ber. 70/7, 1997, No. 7, 211-219); L1999 Antike Glastöpferei (chapter on cameo glass with contributions by Mommsen, Simon, Weiss; English summary); L2002b (internal scratches, scientific investigation by RGZM and Fraunhofer Gesellschaft); L2004a (contribution to a discussion in ‘Minerva’). L2009b The non-blown ancient glass vessels (chapter on cameo glass). L2011b (updated summary of Lierke cameo publications; English summary); L2011a (online) Sir Popper and the Portland Vase.

Hot forming of cameo glass - the principle

model * plaster mold * powder-filled * hot glass * pressing * sagging * rim flows * rim narrowed * cooled

The hot forming of cameo glass contradicts the opinion which prefers to consider the cameo glass vessels as ‘masterpieces of the art of glass cutting of all times’. But, the decision is not a question

of believing or not believing, it is a question of a sober evaluation of controllable facts. Everybody interested may have a closer look at the originals and make up his mind from their manufacturing marks.

One of the most important results of many years of investigations was to learn that the early Roman

cameo glasses were not cut from a blank with two differently colored glass layers. Instead, they were most probably formed hot, using glass powder for the cameo decor. The process is related

to the manufacturing process of Terra Sigillata - using easily crumbling one-time usable plaster molds instead of reusable ceramic molds.

The visible manufacturing traces and their explanation

Some features of the two impressive cameo vessels in the British Museum, the Auldjo Jug and the Portland Vase, could easily be detected by any attentive visitor of the museum:

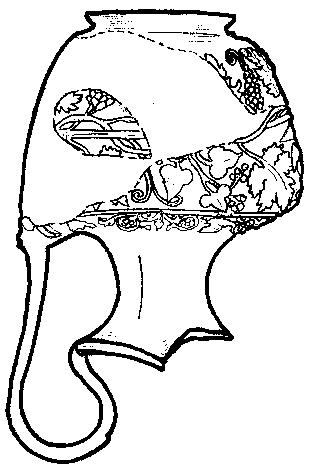

The Auldjo Jug:

1. The handle is connected - not applied - to the vessel at its upper end. Handle and vessel are one piece of

glass (this was confirmed by M. Bimson in D.B. Harden JGS 23, 1983, 51). What does this mean? The vessel and the handle are obviously formed at the same time. The handle was not

applied subsequently as is customary with blown glass. It was cut or pressed from a one-sided much longer neck. This is supported also by the obviously pressed - not cut - pattern on the

handle. At its lower end, the handle was applied with some hot glass to the already existing decor. This decor was not cut later. 2. 3. The white

ring with rounded surface around the middle of the vessel is wavy (see above right). What does this mean? A ring cut from a cold cutting blank would be traced on the blank first,

and therefore be level and straight. A cut ring would most probably not have a rounded surface, since any rounded protruding feature must be ‘modeled’ with numerous tiny cutting facets. This

requires a tremendeous amount of work. Obviously, the ring was molded and it became wavy while the glass was still hot. 4. Where the tendrils lost their white decor,  The wall with decor was deformed from the application of the handle. What does this mean? As indicated by the drawing (left), this deformation seems to have

been caused by the weight of the handle while the vessel was positioned upside-down on a mushroom-shaped plaster support during the final manufacturing process. [see

The wall with decor was deformed from the application of the handle. What does this mean? As indicated by the drawing (left), this deformation seems to have

been caused by the weight of the handle while the vessel was positioned upside-down on a mushroom-shaped plaster support during the final manufacturing process. [see  the dark glass underneath becomes visible with a rounded protruding profile - and, the same is true for the partly visible cross section of a leaf

beside an insert (see arrow right). The dark glass can be recognized to intrude into the white glass. What does this mean? A two-layered blown cutting blank would always show an even interface between the

two layers. The dark glass would never intrude into any bulge of the white glass. The Auldjo Jug therefore was not made from an overlay (two-layered) blank.

the dark glass underneath becomes visible with a rounded protruding profile - and, the same is true for the partly visible cross section of a leaf

beside an insert (see arrow right). The dark glass can be recognized to intrude into the white glass. What does this mean? A two-layered blown cutting blank would always show an even interface between the

two layers. The dark glass would never intrude into any bulge of the white glass. The Auldjo Jug therefore was not made from an overlay (two-layered) blank.

Supplement: occasionally it is assumed that the blanks of the cameo glasses are mold blown. This is not possible. No single cameo glass - it may be thin- or thick-walled - shows the slightest relief on its inside as would be expected at any mold blown glass.

The Portland Vase: Only few manufacturing traces are visible at the

Portland Vase, because of its history of several restorations. It bears now a high gloss polish which is without comparison, and which probably was applied

during an early restoration. The few traces, however, are sufficient to preclude a cutting of the cameo decor. 1. It is striking that the horns at the lower attachments of the handles

remained uncut. This was firstly described by 2

. No defects caused by grinding or cutting are visible, however, modelling flaws could be discerned. For an example see text I, 3. To the right side of this foot are slightly slanting and extremely vertically stretched bubbles visible

in the dark glass, while the bubbles nearby in the white glass of the vessel are nearly round. What does this mean? In a two-layered blown cutting blank, the bubbles in both layers should have

about the same deformation or none. This means again, the Portland Vase was not made from a two-layered cutting blank [see also

Both cameo vessels - as a matter of fact all early cameo vessels - have no cameo decor at the handles, at the neck or at the rim. Not visible to a visitor are the typical traces on the inside of

these vessels which are significant for the manufacturing process. In the literature, the traces are seldom mentioned and - if mentioned - so far not correctly explained (Portland Vase: internal

traces occasionally mentioned as ‘grinding marks’, correct would be ‘rotary scratches’, see text I,3; Auldjo Jug: vertical traces in the neck mentioned as ‘blowing striations’(unparalleled in other blown vessels!), better would be ‘flowing striations’ [Harden JGS 25, 1983; L1999, fig. 175; L2009b, 67].

The internal traces distinguish the two vessels - as well as all other early cameo glasses - from blown glass. All manufacturing traces which have been mentioned here could be explained by hot-forming of the cameo glasses as shown

above.

In cooperation with scholars of different scientific background, the problem of the cameo glass manufacturing was thoroughly investigated. The support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

enabled investigations of original vessels and fragments and some

A special thank is addressed to all who made it possible - despite a different opinion - to investigate original vessels

and fragments in their care. Some cameo plates, 12 cameo vessels and about 200 fragments exist. Thereof 6 vessels, 2 plates and numerous fragments were privately investigated. My thank is dedicated especially to the British

Museum for several investigations (Dr. V. Tatton- Brown and Dr. Paul Roberts). Last update January 19, 2007

The following text (here with few additions) was presented as part of a poster at the 15th congress of the AIHV, New York/ Corning Oct. 15-20, 2001, but a summary of the poster texts was not printed in the Annals. If you like to make citations, please mention author, congress and web site with date.

I Cameo glass – more evidence of molding 1. Elongated bubbles

in the blue glass were mentioned as proof that the blank of the Portland Vase was blown [W. Gudenrath and D. Whitehouse, The manufacture of the vase and its ancient

repair, J. Glass Studies 32, 1990, p. 109, Fig. 67, showing lower part of right leg with foot of seated female figure and vertically stretched bubbles in the neighboring blue background].

However, in the lower wall area of a vessel, the bubble distortion is about the same whether this vessel was blown and stretched or pressed. Something else is important: Since the two layers of

an overlay glass are blown together, bubbles in both layers should endure about the same distortion. In our case: if the Vase was blown and the bubbles in the blue glass are elongated, the

bubbles in the white glass should be elongated about the same. But, the bubbles in the white glass in the same area are round. This is best to be checked at the original vase, but it is visible also on

the photo mentioned above. This feature was not regarded yet, but it is easily explained by the proposed molding process [see

The white glass powder is held in the cavities of a plaster mold while the blue glass is pressed as very hot lump into this mold. The white glass will melt from the heat, but not move from its place.

Therefore, bubbles in the blue glass may get stretched, but the bubbles in the white glass will remain round. Plaster molds do not stick to the glass and crumble easily after enduring the contact with the hot glass. 2. The right foot [of the seated figure mentioned above, here shown as a detail from the front cover of 3. Typically, the inside of early Roman cameo glass is wholly or partially covered with rotary scratches

. It was assumed that the cause of these horizontal striations on the inside of the Portland Vase was ‘internal grinding’ to test for or to remove stress [W. Gudenrath and D.

Whitehouse, The internal grinding of the vase, J. Glass Studies 32, 1990, p.137]. Because this opinion is still occasionally cited, I shortly repeat an earlier reply [

Supplement: In the meantime appeared:

Ursula Liepmann, Ein augusteisches Kameoglas im Kestner-Museum zu Hannover. Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte Bd. 41

(2002) S. 9 – 36. With detailed technological, stylistic and chronological considerations and investigations, an object from the collection of August Kestner is presented. Here as supplement to

the text above, a feature shell be mentioned which is known from other examples as well: the relief proceeding into the dark background. The cameo fragment from Hannover shows two male

figures, one of them with a comparatively flat hair-do. A close-up view reveals that the hair-do is partly in dark relief. This detail hardly could be explained here as intentional stylistic feature with a

mystical effect, showing the superior quality of the glass cutting - as was done concerning other examples. By hot-forming, such a feature appears - with or without intention - if a cavity in the mold

was not filled with enough white glass powder to cover the dark background after melting. [see the illustration of a small experimental cameo plate Glass pottery / illustrations f]. U. Liepmann shares

this last explanation. She also found other details in agreement with the hot-forming of this object.

R. Lierke, August 13, 2003

Other publications confirming the hot forming of cameo glass are mentioned on the

The following text (here with few additions) was presented as part of a poster at the 15th congress of the AIHV, New York/ Corning Oct. 15-20, 2001, but a summary of the poster texts was not printed in the Annals. If you like to make citations, please mention author, congress and web site with date.

II

How about an earlier date for some cameo glasses? A little detour leads to cameo glass vessels. Closed ‘agate’ or ‘banded’ glasses without

remarkable traces of a core exist probably since the 2nd c. BC already. However, the small glass tubes used for blowing the first tiny and thin-walled glasses in the 2nd half of 1st c. BC could never

be used to pick up and inflate a thick-walled prefabricated blank for an ‘agate’ glass vessel. The first sturdy metal blow tubes obviously were not used earlier than in the second half of the 1st c. AD

for cinerary urns. The ‘agate’ glass vessels and the well known gold-band bottles among others are proof, that it was possible to produce hollow vessels without blowing. Both vessel types

occasionally feature internal ‘flowing striations’ in the neck - which are also known from some cameo glasses, but unknown from blown glass. [

In any case, the technological preconditions to make cameo vessels were given already before the last quarter of the 1st c. BC. It was possible to mold glass cameos, and it was possible to make

hollow vessels without blowing and without adhering core. Both abilities had to be combined. The few extant ‘early Roman’ cameo glass vessels are all dated today late 1st c. BC/first half 1st c. AD.

Only the Corning cameo lagynos no. 68.1.1 (assumed origin: the eastern Mediterranean), was indeed cautiously assigned by A. Oliver to late 2nd /1st c. BC [A. Oliver Jr., Glass Lagynoi, Journal

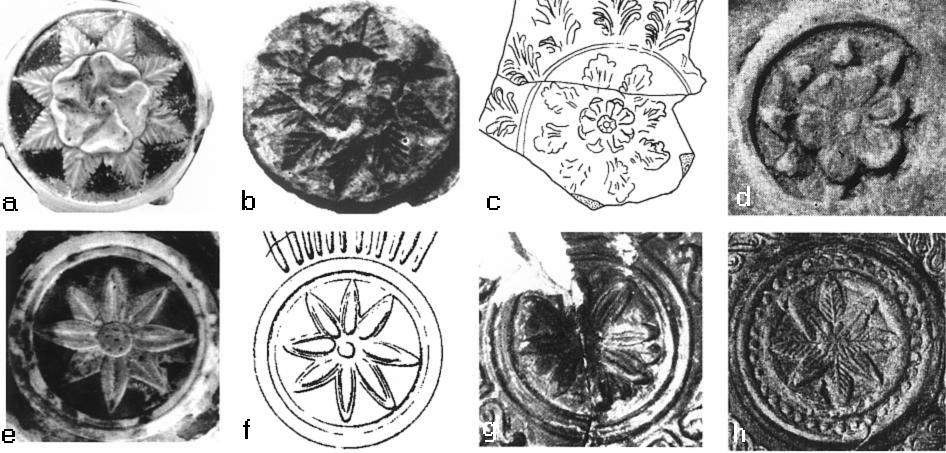

of Glass Studies, v.14, 1972, pp. 17-22]. Its numerous ceramic parallels are dated 3rd/1st c. BC. Searching for ceramic parallels for other cameo glasses brings astonishing results. The bottom

rosette of the small bottle in the Getty Museum (a), said to be from Eskisehir/Turkey, almost fits into a mold fragment from Kyme near Izmir (b) which was dated by J. Bouzek to about the 2nd quarter 2nd

c. BC. It resembles many rosettes from ‘Megarian bowls’ (2nd c./first half 1st c. BC), see the examples c, d. The latter applies as well to the 8-pointed star rosette of the Morgan cup in

the Corning Museum (e) which is said to be from the Turkish Black Sea coast - see examples f, g, dated 145-100 BC, or 2nd/3rd quarter of 2nd c. BC. The cameo glasses were not necessarily

made at the same date as the ceramic vessels with comparable decor elements, but the possibility is suggested that some cameo glasses may be older than previously thought. Bottom

rosettes of ceramic vessels do not occur after the Megarian bowls.

Molded relief ornaments of Egyptian faience or glass were known at least since the 18th dynasty in

Egypt. Faience was made from powdered constituents, while glass was either sintered from glass powder or pressed from reheated chunks of raw glass. In Ptolemaic times, the molded glass inlays

became quite sophisticated. No wonder that the first cut cameo stones became an inspiration for this art too. Several three-layered glass cameo portraits of Ptolemaic kings are known, dated early 2nd/ first half 1st

c. BC [D. Plantzos, Ptolemaic cameos of the second and first centuries B.C., Oxford Journal of Archaeology, v. 15, no. 1, 1996, pp. 39-61]. There is hardly any doubt that these

were made in the tradition of the just mentioned molded relief ornaments. Their appearance equals other three-layered molded glass cameos. The use of glass powder for the cameo decor

was confirmed for those – fully in agreement with independent investigations by C. Weiß [see Lierke in

L1999 p.77-79 and C. Weiß in

L1999 p.80-82].

Bottom rosettes of cameo glass vessels (a and e) and relief ceramic bowls # a) cameo balsamarium, last quarter 1st c. BC/1st quarter 1st c. AD, Paul Getty Museum acc.

no. 85 AF 84 (D.B.Harden et al. Glass of the Ceasars 1987, p. 83-84, photo courtesy museum). # b) ceramic mould fragment, 2nd/3rd quarter 2nd c. BC (J. Bouzek, Anatolian coll. of Charles Univ. 1974, pl.2/14. # c

) Megarian bowl, 1st half 2nd c. BC (G. de Luca, W. Radt, Sondagen im Fundament des Altars, Pergamenische Forschungen v. 12, 1999, Beilage 13/530). # d) Megarian bowl (Bouzek, cp. b), pl. 5/25). # e

) Cameo bowl, 1st half 1st c. AD, Corning Museum of Glass acc. no. 51.1993 (D. Whitehouse, Roman Glass in the Corning Museum of Glass, v. 1,

1997, p. 48-51). The same vessel was dated by E. Simon: ‘3rd quarter of the 1st c. BC or earlier’ (J. Glass Studies v. 6, 1964, pp 13-30). # f) Megarian bowl, dated 145-100BC (S. Rotroff,

Hellenistic Pottery: Athenian and Imported Moldmade Bowls, The Athenian Agora, ASCSA 1982, pl. 87/322). # g) Megarian bowl, ~1st half 2nd c. BC (Bouzek cp. b), pl. 7/44). # h )

Megarian bowl, 2nd or 3rd quarter 2nd c. BC, Nationalmuseum Athens, acc. no. 14624 (U. Hausmann, Hellenistische Reliefbecher aus attischen und böotischen Werkstätten, 1959, ppl. 37/2) It is striking also that all cameo glasses and all ceramic parallels mentioned so far, have or are

assumed to have an eastern origin. The same is true for two more cameo vessels, a skyphos or rather goblet kantharos in the Getty Museum, which is said to be from a Parthian tomb in Iran, and

is dated last quarter 1st c. BC/1st quarter 1st c. AD [in Harden et al., Glass of the Caesars 1987, p. 68 ], and in addition a small vessel of the same type [see the

D Home Publikationen G lastöpferei Techniken Kameoglas Diatretglas H edwigsbecher Craqueléglas Werdegang D

E EnglishHome Publications GlassPottery Techniques CameoGlass CageCups HedwigBeakers Craquele Vita E